With the climate crisis intensifying and heat records breaking annually, the search for solutions is urgent. In the halls of international climate summits, one technology is now hailed as a potential game-changer: Direct Air Capture (DAC). This process scrubs carbon dioxide from the ambient air, promising to undo the damage we have wrought. But is it the miracle we await, or a dangerous distraction that allows polluters to continue business as usual?

The allure of an easy fix

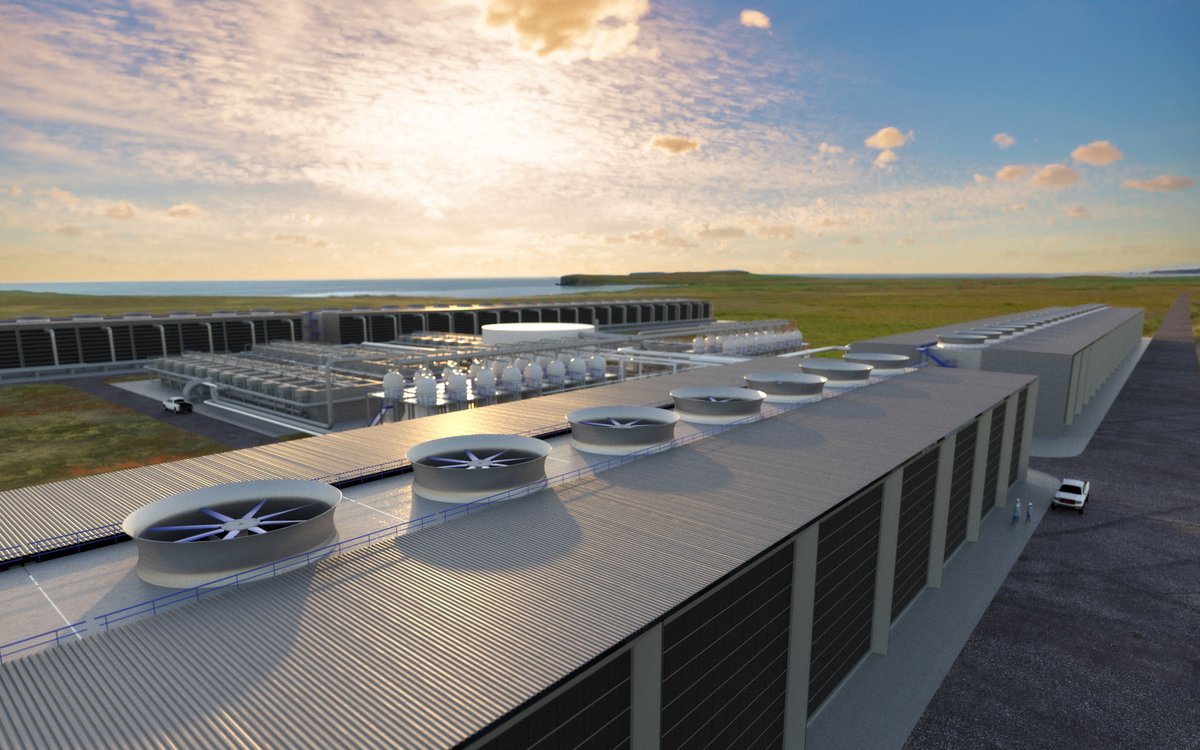

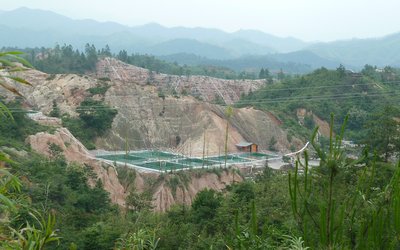

The premise of DAC is compelling. Large facilities use giant fans to pull air through filters that chemically bind with carbon dioxide. The captured carbon can then be stored deep underground or used to create synthetic fuels, removing it from the atmosphere or recycling pre-existing atmospheric carbon.

For companies and industries where fossil fuels are heavily ingrained in their business models, DAC offers a path to “net-zero” without a complete infrastructure overhaul. It is a techno-optimist’s dream: a machine that cleans up our mess for us, buying the world time to transition to a greener economy.

The thorny reality

This dream faces practical challenges. The first is cost: capturing a tonne of carbon dioxide from the air, where it is very dilute, is immensely energy-intensive and expensive. Current electricity prices mean that powering the technology could exceed $600 per ton, though proponents hope to reduce this. In fact, the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is now subsidising the technology at $180 per tonne, a massive public investment to spur DAC’s development. This leads to the second problem: scale and capacity. Powering DAC plants with fossil fuels would be self-defeating, creating more emissions to capture others. This leaves renewable energy as the only viable option, renewable energy at a scale that the world does not have yet, because global emissions total tens of gigatonnes annually. Making a meaningful tool would require an unimaginable number of DAC plants, and powering a global DAC network with clean energy would require land equivalent to entire countries.

Consider the Stratos project in Texas, developed by Occidental Petroleum. Once operational, it is designed to be the world's largest DAC facility, capturing 500,000 tons (0.5 megatons) of CO₂ per year at a cost of over $1bn to construct. This is a monumental feat of engineering, yet its annual capacity is a tiny fraction — roughly 0.01% — of the net 600 megatons (0.6 gigatonnes) that our natural carbon sinks absorb each year. Such investments ultimately beg the question: is the international community using their time and money to invest in the most effective and efficient solutions to climate change?

A view from the Congo Basin

This is where the perspective from a nation like the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) becomes critical. While the Global North invests billions in new machines, the DRC already hosts one of the planet’s most powerful carbon capture systems: the Congo Basin rainforest. The Congo Basin is the world's second-largest “lung”, a natural sink whose peatlands alone store 30 billion tons of carbon, equivalent to three years of global fossil fuel emissions. The argument from the DRC and other forested nations is powerful. Why spend fortunes to build expensive artificial carbon sinks when we already have highly effective ones, for free, at our disposal? This brings into focus a stark question of global justice and financial priority.

The U.S. government's $180/ton subsidy for DAC technology will cost hundreds of billions, primarily benefitting wealthy tech firms and oil corporations like Occidental, who are hedging their bets on fossil fuels. The international funding for wildlife conservation pales in comparison. The Central African Forest Initiative (CAFI), a major fund for the Congo Basin, has received pledges of only $1.5 billion over multiple years and for multiple countries — a figure dwarfed by the investment in a single DAC plant.