On June 13, 2025, concertgoers waited breathlessly for a concert by Ukraine’s 2007 Eurovision finalist Verka Serduchka. Anticipating nostalgia, they met controversy instead; Serduchka decided to not alter any of his discography for the performance, playing his old hits in original Russian. Many fans and fellow artists expected him to translate the songs into Ukrainian as a symbolic gesture of cultural solidarity prior to the show, and backlash was swift.

This is just one example of a broader cultural shift in Ukraine. The slow retreat of Russian and Surzhik (a Russian-Ukrainian hybrid) tells a deeper story — one of identity, resistance, and national awakening, sharpened by years of conflict with Russia. While this shift toward cultural autonomy might appear to undermine Moscow, President Putin has seized on it as fuel for his propaganda machine.

A hard habit to kill

Historically, the Russian language was used as the glue of the Soviet Union to maximise cohesion and integration. Across the USSR, regardless of the region’s native language, classes in schools and universities were taught in Russian. Many students, up until the collapse of the communist regime, moved to Russia for better opportunities and resources. Due to decades under Soviet rule, many post-Soviet nations continue to speak Russian to this day, and Ukraine is no exception. For many Ukrainians, Russian isn’t just a second language; it’s the one they use most in daily life, particularly in the southern and eastern regions of Ukraine. As of 2022, 18% identified Russian as their mother tongue and primary language.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine has experienced a steady push for de-Russification, with the Ukrainian language gaining ground in daily life through societal and legislative efforts. In 2019, Ukrainian was officially declared the country’s sole state language: a symbolic move underscoring national independence and cultural self-determination. Yet, Russian continues to play a significant role in many people’s daily lives. Aside from cultural heritage, Russia remains a major economic attraction for those who are able to speak Russian. Russia — as the centre of the Soviet Union — still holds a disproportionate share of professional opportunities, access to funding, advanced education, and medical infrastructure in the post-Soviet space. And for many Ukrainian artists, ceasing to produce content in Russian or cutting ties with the Russian market means risking a significant loss of audience and income.

Finding Ukraine’s voice

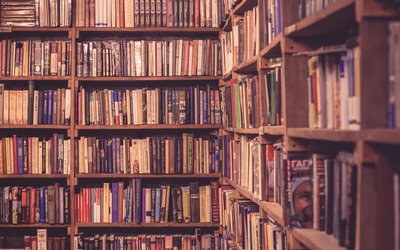

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine is the most recent catalyst for a new wave of rejection of Russian and Surzhyk. It is now seen primarily as the language of the aggressor, and therefore for many Ukrainians the rejection of Russian has become a moral duty and a psychological necessity. It is one way to sever all possible ties with Russia, emphasise their differences, and project unity at home. Books written in Russian were removed from houses and destroyed on local initiative; cultural figures who used to work in Russian, or with Russia, have completely switched to Ukrainian; and on a household level, many families are actively phasing out Russian from their daily speech.

This newfound linguistic solidarity within Ukraine is visible far beyond its borders. While other post-Soviet countries have been gradually distancing themselves from Russia and promoting their national languages, Ukraine’s case has become especially notable due to the war. The full-scale invasion turned language into a geopolitical issue, which prompted Europe to visibly acknowledge Ukrainian. Ukrainian is now appearing in European museums, on government websites, and as a language option on global platforms like Netflix, and not because of user demand.

Nevertheless, the trend of Ukrainians abandoning Russian in their country is not unanimous. Some, including celebrities like Verka Serdyuchka, openly declare that they are not ready to cut ties with the Russian language only because they happen to be at war with their neighbours who speak it. Such statements have caused heated debates and sharp reactions from fellow citizens, like when a formal complaint about the concert was filed with Ukraine’s Language Protection Commissioner. Though ultimately dismissed, because Serdyuchka had no affiliations with the Russian state, it proved a point.

Yet dropping Russian is not always an easy “choice”. For people in predominantly Russian-speaking cities like Kherson, Odessa, Donetsk, Luhansk, Kharkiv, and Zaporizhzhia, many people barely speak Ukrainian. Yet they now find themselves heavily judged, even as they are amongst the hardest-hit by the war.

Playing into Putin’s hand

Counterintuitively, the majority of Ukraine’s fierce rejection of Russian is exactly what Putin and other head Russian pro-war politicians seize upon. They use Ukrainians’ rejection of the Russian language as supposed proof of discrimination against Russian-speaking populations. Putin continues to present the so-called “denazification” of Ukraine as one of the key justifications for his “special military operation”. In this narrative, every step Ukrainians take to strengthen their identity through the use of their language, especially when it involves a visible and symbolic break with Russia, is portrayed as evidence of nationalism, hostility, or even ethnic hatred. Russian propaganda frames these grassroots shifts as existential threats. As Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov claimed in March 2022, “It is not uncommon that you have to pay for the right to speak your native language with your work and health, but also with your life”. Such rhetoric helps construct the image of a vengeful, intolerant Ukraine. One that, in the Kremlin’s telling, justifies military intervention under the guise of protecting Russian speakers.

The prior establishment of Ukrainian as the sole state language seems to me a crucial symbol in the country’s path to independence. It’s only natural that the war has triggered such sharp surges of commitment on this issue, a demonstrative rejection of anything associated with Russian. In my view, this everyday categorical stance will likely soften over time, as this collective wound stops bleeding. Ukraine will eventually be able to work toward a balance between strengthening national identity, acknowledging its historical linguistic complexity, and avoiding discrimination against those who continue to speak Russian.