The Chinese have arrived!” my local guide shouted, pointing at the other bank of the Mekong river. He drew a big circle in the air with his finger, in the direction of the Lao side of the river we were crossing. “All Chinese!” he shouted again, trying to be heard over the loud engine of our boat.

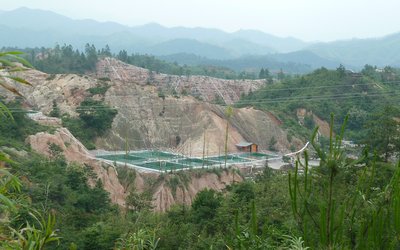

He was pointing to one of the most bizarre landscapes I had ever seen. Emerging from the tropical forest along the river was an entire modern city, replete with skyscrapers and a dozen more under construction. We were crossing the Mekong in the “Golden Triangle” region, where the borders of Laos, Myanmar and Thailand meet. The region was named “golden” when it was the global centre of opium production. Nowadays, it is meant to be free from narcotraffic, although Thai, Lao, and Chinese authorities continue to seize large narcotics shipments traced back here. “What about the Chinese?” I asked myself. “What do they have to do with this place, and specifically, with this futuristic city on the Lao side of the river?”

In 2007 the Lao communist State created several Special Economic Zones (SEZ) aimed at attracting foreign capital and partially opening its economy to the world market. Special tax conditions and looser regulations made these SEZ’s appealing investment opportunities that attracted large capital inflows. The towering skyscrapers overlooking my boat were the clearest example of this model’s success, part of the 3000 hectares wide “Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone”. This SEZ was designed as a joint venture between the Lao government and the Chinese company Kings Romans Group, with Laos participating with a 20% stake. The remaining 80% is held by Kings Romans Group and its owner, Chinese businessman Zhao Wei. Zhao is allegedly involved in money laundering, heroin and methamphetamine traffic, and other forms of transnational organised crime.

High-rises in the jungle

The story of the Golden Triangle SEZ begins in 2007, with the forced displacement of local residents and the launch of construction on a massive casino complex. The construction works rapidly expanded to roads, palaces, hotels, canals, ports and — in true Las Vegas fashion — a small reproduction of Venice, Italy. With its modern architecture and gold detailing, the casino remains one of the largest and most striking buildings in the SEZ, even after a whole city has risen around it. Selecting the casino as the inaugural structure was no accident: it was an strategic move that served both the official and unofficial purpose of the whole SEZ.

The SEZ was founded with the official aim of kick-starting regional development, creating a city which would attract tourists through luxury resorts and entertaining nightlife. Given that most forms of gambling are prohibited in both China and Thailand, constructing a casino between the two is seen as a savvy exploitation of jurisdictional ambiguity. To facilitate the arrival of tourists from all over the world (though largely Chinese), a full-sized international airport terminal is being built close to the city. By drawing people from across the region, the city has become an unlikely ethnic mosaic. Though situated on Lao territory, its construction sites are filled with low-skilled workers from Myanmar, while high-skilled labour is mostly brought in from Thailand. The developers, and most of the tourists, are Chinese. In fact, Chinese presence is everywhere: The first language in the SEZ is Mandarin, street signs are written in Chinese characters, and ATMs distribute primarily Chinese Yuan, the most widely accepted means of payment. In the eyes of a tourist, the city really looks like a small piece of China emerging in the middle of a Lao forest.

From heroin to high rollers

Critics point out that there might be some shadier reasons for the huge Chinese investments in this particular SEZ. The Golden Triangle, known famously for drug production and human trafficking, makes a loosely regulated casino particularly useful to launder dirty money crossing its three borders. The geographic position of the gambling centre is any money launderer’s dream: the casino is only a couple kilometres away from Myanmar, the world’s second largest exporter of opium. It is also immediately in front of Thailand, Myanmar’s largest recipient for drug trafficking.

To a Western observer, the story of a city emerging from the middle of nowhere, centred around gambling, tourism, and money laundering by criminal organisations is nothing new. The description matches 1950s Las Vegas perfectly.

It’s hard to assess objectively how much these operations are harmful or beneficial for the Lao population and the region’s economic stability. On one hand, official statements by the U.S. express high concern about the casino, calling out Zhao’s actions in the area as “horrendous illegal activities”. They describe a tragic situation for local farmers and fishermen, who have been deprived of their property and their ability to conduct business by the construction of the SEZ. Zhao responded to the accusations by marking them as a “hegemonic act of ulterior motives and malicious rumour-mongering”. Whilst it is true that U.S. accusations may be driven by geopolitical ambitions, the Lao support for Zhao must be understood through the prism of growing Chinese influence in the region; more than half of Lao public debt is in the hands of the neighbouring superpower, and most of the electricity-generating dams on the Mekong affluents are in the hands of Chinese enterprises. Such a relationship can be mockingly summarised with the sign at the border between the two nations: “Long live the friendship between Laos and China”.

A new Asian Las Vegas, a money laundering paradise, or a symptom of a strong Chinese hegemonic influence — the Golden Triangle SEZ might be some, or all the above. The project certainly brought great opportunities of growth to the region, but with that the creation of an environment in which existing local criminal networks could thrive and expand. My guide’s shout echoed in my brain. “The Chinese have arrived!” They certainly had, and they are not leaving anytime soon.