Corruption in successive governments is greatly responsible for the underdevelopment of Sierra Leone. It must be totally eradicated if this nation wants to develop as Western and Asian ones have. It is widely asserted that the endemic corruption of Sierra Leone was the root cause of its civil war in 1991, which resulted in eleven years of violence and unrest. How corruption became so bad that it had eaten into the very fabric of Sierra Leonean society must be studied, so that we can resist the rise of corruption today.

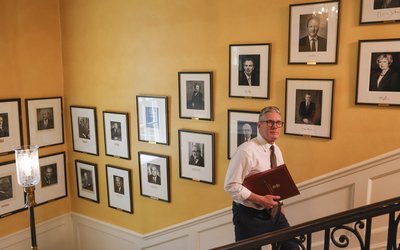

Siaka P. Stevens took office as prime minister in 1968 — only seven years after Sierra Leone gained independence from British rule — and under his rule corruption was institutionalised. By 1978, he had consolidated absolute executive authority by declaring a one-party state under the All People’s Congress Party (APC). This move allowed Stevens to act unilaterally — through patron-client networks, he undertook illicit mining deals at the expense of ordinary Sierra Leoneans by diverting state contracts and syphoning resources abroad. Sierra Leone’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission revealed that corruption was so endemic in Sierra Leonean society that an estimated $160 million were lost from the country’s diamond revenues each year.

Siaka Stevens' consolidation and legitimisation of corruption penetrated the nooks and crannies of social and political structures in Sierra Leone to the point that corruption was present in every facet of society: schools, hospitals, the marketplace and the legal system. Those who watched their leaders' misconduct go unpunished copied these corrupt practices without fear of legal action; governmental structures crumbled, public services and basic amenities perished, the education system deteriorated, and societal trust collapsed.

By the early 1990s, decades of brutal mismanagement had caused the Sierra Leonean economy to crumble. According to the U.S. Embassy, in 1991, inflation was over 100 per cent, the debt service ratio was 50 per cent and a domestic debt of $1 billion. Rampant food shortages occurred, with the majority of the families unable to feed their homes. Neighbourhoods pooled small amounts of money to buy a single bag of rice, or stood in long, exhaustive queues to buy toothpaste.

This public anger spiralled into a thirteen year civil war. The UN Development Programme reported casualties numbered 70,000, with an additional estimated 2.6 million displaced. The war stagnated Sierra Leone’s ability to develop compared to other sub-Saharan nations.

The war demonstrated the destructiveness of corruption. Post-war Sierra Leone experienced a societal awakening. In the early 2000s, President Kabba established the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC), and led the reformation of strategic governmental structures. Unfortunately, a culture of corruption; political interference and disapproval; entrenched patron-client networks; weak accountability; and a lack of transparency meant the ACC made only limited progress. It earned the nickname, “the toothless bulldog”, and immediately after the new presidential election in 2007, high-profile audits surfaced showing suspicious loans and missing international aid funds across ministerial offices, yet accountability remained visibly slow to arrive. In 2008, this was remedied and the ACC was given prosecutorial powers and a stronger legal framework.

Yet the improvements were short-lived. The decade of civil war that Sierra Leone experienced did not solve the tribal sentiments and culture of nepotism that made corruption so prominent. These ideas, and the cultural and governmental infrastructure to carry them out, were mirrored by current leaders, Koroma and now Maada Bio, who learnt from Stevens’ legacy to take advantage of the government.

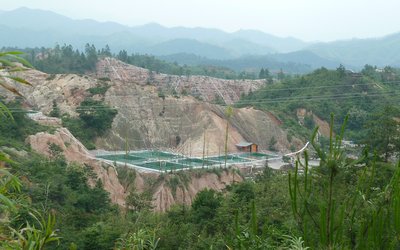

Just like Stevens, Koroma is believed to have benefited from secret deals that diverted 30% of diamond and iron ore revenues from mining companies like African Minerals and London Mining to offshore accounts. His leadership style included ‘signature bonuses’ for his ministers that were disguised as consultancy fees.

Corruption has now extended down to every function of government, no matter how small. Take the medical sector, meant to help the ill. It was fraught with large-scale embezzlement through inflated Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) contracts awarded to APC-linked firms, shady medical supplies and ghost isolation centres, which never existed despite being fully funded. The most prominent example was the embezzlement of international funds to combat the Ebola virus, which were intended to help mitigate outbreaks.

Local journalists reported that the education sector also faced significant corruption scandals, including a particular case where scholarships and government grants were handed out to students who carried party membership cards. Textbook funds were similarly misused between 2010 to 2015, often redirected to print materials for party propaganda.

Infrastructure was another endemic case of corruption, climaxed in Koroma’s infamous Mamamah Airport project, resulting in large sums flowing via Lebanese intermediaries, which was eventually cancelled due to concerns over debt servicing. Road construction also became coveted. Some road contracts were believed to have been awarded to non-existent companies, with 63 ghost contractors identified in the 2017 Auditor General’s report.

Even presidential pardons were compromised. Between 2012 and 2017, Koroma granted pardons to several convicted criminals whose records stemmed from large-scale corruption. The subversion of Koroma’s judicial system penetrated the highest echelons of his regime with the unconstitutional sacking of his vice president, Samuel Sam-Sumana. The ACC reported that Koroma's corruption extended to the electoral system, manipulating voter registration by creating 300,000 duplicate IDs and diverting $28 million to fund APC campaigns.

People hoped that President Julius Maada Bio would represent a departure from Koroma’s style of governance; 72% of officials from Koroma’s regime retained positions of power via rebranded NGOs and shell companies. Corruption has not been quashed. Although the ACC recently recovered a sum close to $1.5 million of stolen public funds under Bio’s governance, critics argue that fines were selectively enforced, leaving Bio’s loyalists untouched.

The current regime has basically copied the strategic corruption schemes of the past. Like President Koroma’s handling of Ebola funds, President Bio is equally criticised for the misappropriation of COVID 19 funds, with $2.5 million unaccounted for in the pandemic relief as per the Auditor General’s report of 2021. In the education sector, Section 4.3 of the 2022 Auditor General’s report highlighted that a whopping sum of $32 million of Free Education funds were flagged as unsupported expenditures.

Thirty years after the end of the civil war, it appears not much has changed. Stevens’ was a brutal and corrupt dictator who presided over a system of nepotism, gluttony, inept leadership, and embezzlement of public funds. Maada Bio and Koroma intend to keep his legacy alive.

Yet bad governance is not a fate that the Sierra Leonean people are destined to. Before colonialism, Sierra Leone was not characterised by corruption. Unlike typical African societies, ruled by noble kings and queens, Sierra Leone had a diverse leadership structure. The country had leaders whose source of power was deeply rooted in the pristine teachings of the customs and traditions of their ancestors. It was only with the introduction of foreign influences that corruption infiltrated the corridors of Sierra Leonean society. We must embrace the legacy of our ancestors, who were known for good governance and the enforcement of cultural ethics with strict discipline, integrity, and compassion.

Corruption is responsible for handicapping our nation. From the British exploitative 'hut tax' to the very first stolen diamonds and public funds syphoned by Stevens, to the unaccounted funds for development under the Bio-led government, corruption has not merely been a crime, but a system, a way of thought, a way of living, and a way of ruling. It is as much structural as it is psychological. It is a system that is inherited not because the people prefer it, but because resisting often comes at too big a price. And yet, it must be resisted.