We’re entering the age of “Green Wars,” and no one is immune. Tanks, punishments, and cyberattacks are no longer the only tools used in wars today. They are increasingly being fought through sustainability regulations, corporate boycotts, and climate policies. What used to be the domain of ethics committees and environmentalists has now spread to the highest ranks of international governance. Environmental, social, and governance policies, known collectively as ESG, have subtly emerged as one of the most effective means by which the relationship between the private and public sector interacts.

Although the concept of using environmental policies as political leverage is not new, the current pace and scale of implementation is unusual. In addition to being morally right, governments and businesses are embracing ESG principles because they are strategic. Controlling the sustainability narrative has the power to isolate rivals, change investments, and influence trade agreements. In certain situations, it may even shift the world’s balance of power.

Small actions, large implications

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), an EU policy that levies import taxes according to carbon emissions, offers a clear window into the way which nations are using green policies to change international trade. Ostensibly, this policy was enacted to fight climate change and promote more environmentally friendly production practices around the world. To many developing nations, CBAM feels more like a trade weapon than an environmental approach. Though presented as a push for global climate responsibility, the policy’s primary function is more strategic than environmental. By enforcing strict green standards, the EU effectively shields its own firms — already compliant with rigorous regulations — while raising barriers for foreign competitors operating under looser rules. The measure disproportionately affects poorer countries that rely on low-cost, carbon-intensive production, curbing their access to the European market. Framed as climate action, it neatly avoids the usual accusations of protectionism. In practice, it is a geopolitical tool wrapped in green packaging. Similar dynamics are unfolding in the corporate sphere.

In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, more than a thousand international firms, including Apple, Visa, and McDonald’s, pulled out of the Russian market. These decisions were not the result of government mandates, but of ESG principles in action. Keen to safeguard their reputations and maintain investor confidence, companies acted swiftly to align with the moral expectations of global stakeholders. According to research from the Yale School of Management (2023), this was one of the biggest corporate migrations in modern history; an active demonstration of how large corporations can now act as a global political force and impose economic sanctions without a government's directive. Thanks to ESG, corporate social responsibility has now become a soft power tactic.

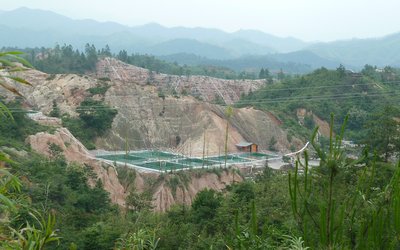

Meanwhile, the global scramble for resources is fuelling the transition to renewable energy, creating new conflicts. Rare earth elements like cobalt and lithium — which are necessary for batteries, solar panels, and electric cars — are in high demand as the globe shifts away from fossil fuels. A large number of these resources are sourced from politically unstable areas, particularly the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which supplies more than 70% of the world's cobalt. The DRC has drawn international attention because of problems like child labour, hazardous working conditions, and environmental damage caused by mining activities. China, an uneasy pillar of world order, controls a substantial portion of the world's rare earth refining market, also making it a significant player in the development of green technologies. Global inequality has increased, and concerns about neocolonial exploitation have been heightened by the competition for access to these vital resources.

It appears that green energy merely moves conflict rather than eliminating it. By attracting economic forces further into resource-rich areas, especially without adequately resolving the local social and environmental consequences, the clean energy transition may occasionally exacerbate geopolitical tensions.

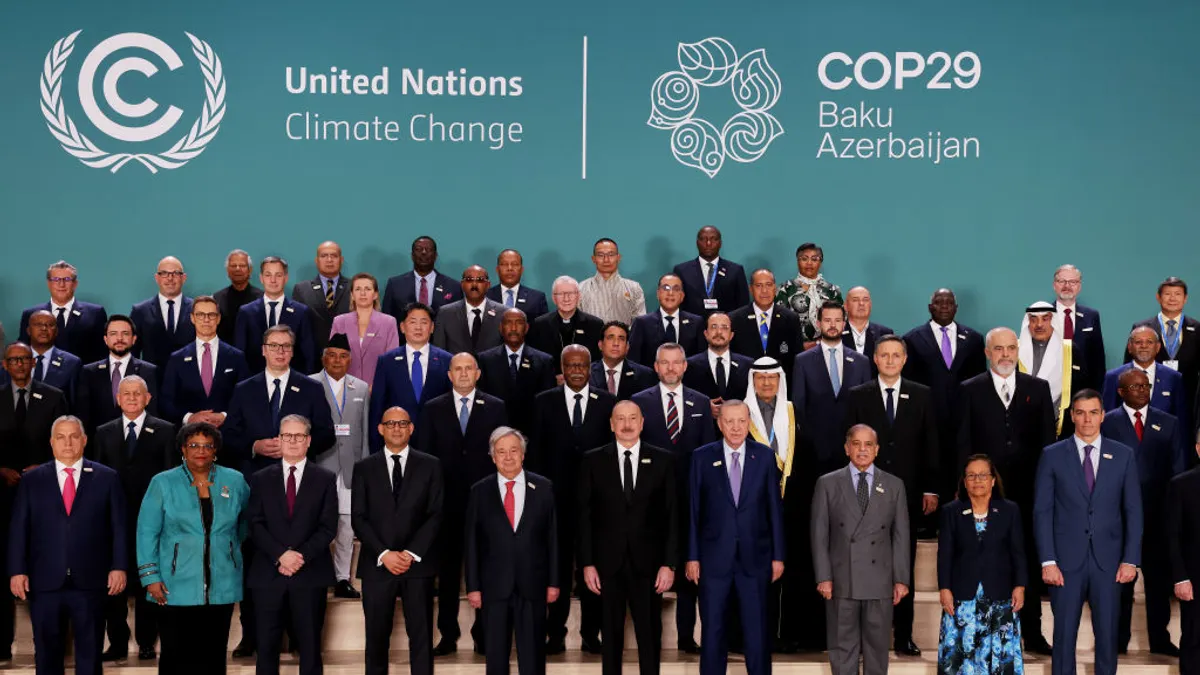

The climate front line

Climate change is increasingly viewed not just as an environmental crisis, but as a threat to global security. As extreme weather disrupts food and water supplies, it drives migration, destabilises regions, and heightens the risk of violent conflict. The UN Environment Programme reports that climate-related unrest is already unfolding in parts of South Asia, the Middle East and Africa. In fragile states, environmental stress can act as an accelerant — exacerbating existing tensions and overwhelming weak institutions. Some governments are using climate emergencies as a pretext for expanding political or economic control. What once were seen as natural disasters are now firmly on the radar of security agencies.

The social aspect of ESG is being weaponised too. Businesses are under increasing pressure to take action on social justice, diversity, and human rights issues. This can lead to tough decisions, particularly when conducting business in nations with distinct political ideologies. For instance, worries about forced labour in Xinjiang have caused some Western businesses to come under fire for conducting business in China. Others face criticism for continuing to operate in nations with anti-LGBTQ+ legislation or with poor governance. Every move made on the global chessboard of social responsibility could have not just political but economic repercussions. Critics unhappy with a company’s operations or marketing no longer complain to friends and family, but spark entire swathes of people to abandon a company’s products. Companies are accustomed to weighing political risks against profits. Increasingly, the two are one and the same.

This global ESG shift has significant implications for commerce students. These days, geopolitics influences every business decision. Accountants need to view ESG reporting as a tool for transparency and international trust, not just a box to check. Marketing experts must recognise the difference between greenwashing, which can result in legal disputes and public scandals, and genuine sustainability promotion. When choosing whether to remain in controversial markets or leave in order to safeguard their brand, managers must balance political reputation against profitability. The impact of green policies on trade, inflation, and inequality is posing new challenges for economists as well.

For the upcoming generation of corporate executives, it is essential to comprehend these dynamics. Rather than a footnote, ESG continues to grow as the primary topic of corporate reports. “Green Wars” are not centred around conventional warfare, but instead soft power and the material gains it accrues. This power may in turn shape future conventional wars through the power balance it upsets. In this new era, wars might be greener, but they are just as fierce.