As Mark Twain famously stated, “history doesn’t repeat, but it often rhymes”, a rhyme which resonates in the distant echoes of the Soviet 1979 invasion of Afghanistan in Russia’s current war against Ukraine. Moscow’s strategic miscalculations have returned to the global stage. In both cases, military overreach — framed as ideological or humanitarian duty — met with unexpected foreign intervention and fierce local resistance to result in a protracted, bloody, quagmire with long-term geopolitical blowback.

Pawns are hard to kill

Proxy wars remain a fixture in interstate conflicts, with those fighting often pawns at the disposal of stronger neighbours. When former USSR General Secretary Brezhnev launched the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan in 1979, it played directly into the hands of the U.S. and its allies. Anticipating Brezhnev’s move, Washington funnelled arms and cash into the country through Pakistani intelligence services. Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) became the central hub for training and supplying the Mujahideen who were fighting against the pro-Soviet communist government, the People's Democratic Party of

Afghanistan (PDPA). Meanwhile Iran, despite its own revolutionary upheaval, provided support to Afghan Shi’a groups, ensuring influence among communities along their border. By underestimating the determination of outside actors to challenge Soviet presence, Moscow ignited a regional conflict, drew in foreign players, and paved the way for political instability which continues to plague Afghanistan today. The Brezhnev Doctrine — the right to intervene in other socialist nations if they threatened the “interests of socialism” — failed in practice because it assumed ideological solidarity could override local political realities and international backlash.

When Russian President Vladimir Putin first launched his “special military operation” against Ukraine in 2022, he took inspiration from his former USSR predecessor by playing into similar regional problems, using local separatist forces to gain the upper hand against Kyiv. Cities in Russian-speaking regions such as Donetsk and Luhansk fell quickly. Putin was confident; major news outlets reported that U.S. intelligence services predicted Ukraine would fall in one to four days. To international surprise, stiffened by nationalism and aided by Russian overconfidence, Ukraine held. Before the invasion, Ukraine’s prospects for joining NATO and the EU were slim. Kyiv had long been viewed as too corrupt to be fully embraced by the West. Now, in resisting aggression, Ukraine not only won Western arms and support, but accelerated its path towards NATO and the EU if the conflict ends with its independence. Misreading regional dynamics is always costly; even a Russian “victory”, would come at the price of over a million casualties, a severely indebted economy, a dearth of international goodwill, and years of bitter fighting. Recognising the enemy’s ability to rally allies is central to wartime decision-making, and one Russia underestimated.

Fuel to the fire

The Soviet Union’s presence in Afghanistan was not just a military one, but an ideological one as well. The PDPA, guided by Marxist-Leninist principles, attempted sweeping reforms including land redistribution, women’s emancipation, compulsory education, and the replacement of English with Russian in schools. In rural Afghanistan, where religion and tribal authority formed the backbone of identity, these moves were perceived not as modernisation but as an assault on Islam.

Soviet-backed leaders like Babrak Kamal were depicted in political cartoons clutching bottles of vodka, symbolising the “godless” nature of communism, a deliberate insult in Islamic culture. This propaganda brought Islamist groups to frame the war as a jihad against atheistic invaders, attracting volunteers from across the Muslim world.

Many of these foreign fighters built transnational networks during the war, some going on to form al-Qaeda under Osama bin Laden. The Afghan Jihad thus became a training ground and ideological catalyst for future global jihadist movements.

History rhymes

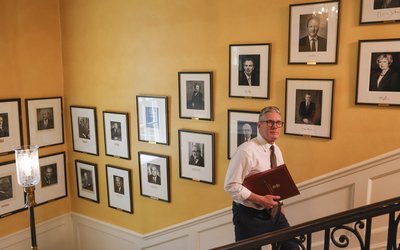

While some argue the Soviet-Afghan War’s legacy is confined largely to history textbooks, it has revealing parallels to the 21st century security situation. Moscow believed in 2022 it could quickly topple Kyiv and install a compliant government, but just like the Soviets in Afghanistan, it underestimated local resistance and misjudged the unity of international opposition. Another important facet was to maintain support at home for these wars. In this case, ideological framing has been just as important.

In Afghanistan, the Soviets claimed they were defending socialism; in Ukraine, the Kremlin claims they are protecting Russian-speakers and resisting NATO “aggression”. These were narratives meant to legitimise intervention but instead hardened resistance, transforming Afghans into guerilla fighters and Ukrainians into determined defenders of their homeland, both with an invigorated sense of nationalism and unity.

U.S. interventions have also shown how “well-intentioned” military actions can backfire. In both Iraq and Afghanistan, the rhetoric of freedom and security clashed with the lived reality of occupation, echoing the gap between Moscow’s justifications of and the actual effects of its war in Ukraine. The lesson for today’s policymakers, whether in Moscow, Washington, or elsewhere, is clear. Military intervention without a deep understanding of local realities, genuine cooperation with local leaders, and careful diplomatic groundwork risks turning strategic ambitions into long-term liabilities.

The Soviet-Afghan War offers a sobering reminder that empires fall not only because of external opposition but also because of their own strategic miscalculations. In the 1980s, those errors unfolded in the mountains of Afghanistan. In the 2020s, they may be playing out again on the battlefields of Ukraine.