Established in 1950, the Charlemagne Prize rewards the architects of European unity. Awarded in Aachen, the former capital of the Frankish emperor, the prize reflects Europe’s quest to endow itself with a founding father. This choice is far from trivial; it is based on a historical vision that presents the Carolingian Empire as one of the earliest forms of continental unification. But why prioritise Charlemagne, a warrior king anointed by the pope, over a figure such as Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-emperor and symbol of universal reason?

A symbolic memory

At the signing of the Treaties of Rome in 1957, some perceived a symbolic rebirth of Charlemagne’s empire, which had been founded in the same city in 800 CE. The borders of the European Economic Community (EEC) partially overlap with those of the former empire: France, Italy, West Germany, and the Benelux countries formed its central core, stretching from the Seine to the Rhine.

This geographical reference is not incidental. It helps to construct an imaginary sense of continuity — a mental map in which contemporary political Europe appears as a natural heir. This territorial memory has fueled the appealing idea of a "return" to an ancient order. The European Union quickly recognised the symbolic power of a figure claimed by both France and Germany, now recast as the embodiment of a shared destiny; an appropriation which follows a long tradition, from French monarchs to the Habsburgs and Napoleon.

The entrenchment of the Carolingian myth owes much to the work of historians. A substantial body of literature, at times scholarly, at times ideological, has emerged in the past years. Pierre Riché described Carolingian Europe as a “moral person”, and a “collection of territories that became aware of their common destiny”. For Itvan Gobry, Charlemagne is quite simply the “founder of Europe”. Alessandro Barbero portrays him as a “father”, in a narrative centred on civilisational lineage.

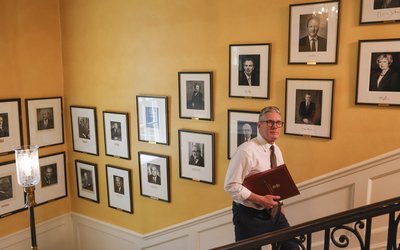

And this active memorialisation by historians has informed political discourse greatly. In 1988, French President François Mitterrand praised a “shared history” born “in this city [Aachen], centre of an empire where Europe’s peoples began to live together” in his acceptance speech of the Charlemagne prize. Only twenty years later, President Emmanuel Macron again invoked this “Carolingian dream” in the name of a sovereign Europe during his acceptance speech. In 2023, EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen spoke of “the weight of European history” felt in Aachen, urging the defence of “freedom, humanity, and peace” in the wake of his legacy. The EU even supports a tourist trail called the “Charlemagne Route” which physically maps this continuity across the continent.

A coherent alternative

But should the EU identify with this Christian, authoritarian, and warlike empire? Charlemagne received his crown from the pope and ruled in the name of God, not the people. His contemporaries spoke of “Christendom”, not of Europe. Historian Johannes Fried reminds us that the term “Europe” held no relevance at the time: Charlemagne did not “create” this union. Despite its reach, his empire covered only a fraction of today’s EU, which extends significantly more, particularly to the east. Moreover, his reign was characterised by violent conquests, rigid centralisation, and forced conversions — a peculiar model for a Union founded on democracy, peace, cultural diversity, and the rule of law.

Europe also claims to be heir to Rome: civil law, neoclassical architecture, an international European citizenship... so why not valorise a Roman emperor? Marcus Aurelius, a Stoic thinker, embodied a different kind of unity than Charlemagne; one grounded in reason and universality, rather than in the sword and the faith. He governed a multiethnic empire structured by durable institutions. His Meditations, in which he advocated for rational governance, still resonate today with principles of duty, tolerance, and responsibility. Principles that, at least in theory, underpin the European project. Certainly, not all European peoples have interest in claims of Roman heritage: the EU today includes heirs of Slavs, Scandinavians, and Celts. And the Mediterranean, once Rome’s heart, is today a point of rupture. Yet the limitations of this model are no greater than those of the Carolingian myth. If we must look to the past, being more exacting in choosing a leader to exalt is prudent.

Why we look to the past

History is a tool. It helps us think about the present, but it should not serve as a flattering mirror let alone a prophecy. It illuminates, but it does not justify everything. In its obsession with finding forebears, Europe risks building itself on fictions. As Jacques Le Goff put it: “Charlemagne as a prefiguration of Europe is a contemporary fantasy! The emperor looked backwards, toward the Roman Empire; today’s Europe must, for its part, look to the future”.