Sir John A. Macdonald, the first Prime Minister of Canada, remains one of the most influential yet disputed politicians in modern reevaluations of Canadian history. January 11th, 2025 marked two hundred and ten years since his birth, and is annually commemorated as a “heritage day” by law, representing his role in the foundation of Canada. Though this date is not a public holiday, it is symbolic in its existence as a marked sign that the nation embraces its first leader.

Recently, very opposing views have emerged when addressing how to remember Macdonald's legacy. Richard Gwyn, his biographer, notes that without Macdonald, no one would even be considered “Canadian”. Whilst others, aware and critical of his record with Indigenous peoples, see this anniversary as an occasion to remember the crimes that continue to tarnish his — and Canada’s — image.

Unifying achievements

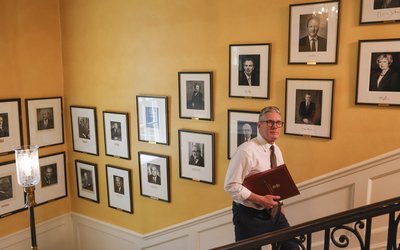

Macdonald, knighted by Queen Victoria in 1867, was an undeniably influential figure in Canadian political history. Dubbed the “father of the Confederation”, he maintained an impressive track record in the Canadian Parliament, having served a total of forty-seven years, including nineteen as the first prime minister. It's without a doubt that the federal system of today stands on the foundations of Macdonald's successful national government and political frameworks.

Understanding his political legacy mainly encompasses the idea of nation building. For instance, Macdonald oversaw the creation of Article content the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP): a paramilitary force to assert Canadian authority, maintain order in the Northwest Territories, and prevent American encroachment. As the first truly Canadian institution, the NWMP served a symbolic role in the representation of national identity. Notably, Macdonald later made significant contributions in uniting Canadian territory through expansion and annexation, and additionally through the construction of the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway, which connected the east and west provinces.

To establish Canada as a country with a national economy, Macdonald introduced the “National Policy”: a protective system of tariffs, infrastructure expansion, and promotion of population growth. In contrast with looming American dominance, this initiative reflected a broader vision of a strong, self-reliant Canada capable of independent functioning.

Though progress under Macdonald remained imperative, it was not without absolution: in order to achieve his vision for the nation, it often meant prioritising national construction and unity over indigenous considerations. On a similar note, he was largely responsible for the containment of the North-West Rebellion (1885), during which the Métis, an Indigenous peoples, rose up against the Canadian government.

Thus, the arguments in favour of celebrating Macdonald as the father of the nation are most often based on a desire to exploit his actions in the context of political or partisan purposes. For example, the former Minister of Canadian Heritage, Mélanie Joly, reaffirmed Macdonald’s importance on the anniversary of his birth (2016), stating, “every year [...] Canadians are encouraged to think about the contribution our first prime minister made toward the creation and direction of our country [...] and his vision for a country that values diversity, democracy and freedom”. This angled display of memory, evoked by modern Conservatives and Liberals, illustrates Macdonald as a unifying and positive figure. A shared appreciation was also present during a 2001 debate on the establishment of a Macdonald and Laurier Day — it was understood that the presence of these great builders would be necessary to face an uncertain, tragic, and violent present, following the 9/11 attacks in the United States.

Effectively, historians like James Daschuk affirm that that “there is no doubt that Sir John A. is the father of Canada,” but that he is also “the father of the dysfunctional state we live in today”.

Between diplomacy and domination

Daschuk’s Clearing the Plains (2013), certainly relaunched discussions surrounding the processes that led to the subjugation of the Indigenous peoples of the Canadian Plains. Overall, he analyses how the interplay of ecological collapse, financial malpractice, ill-intentioned actors, and the government’s racist policies, credited to Macdonald, “basically had Indigenous people locked down so tightly that they became irrelevant after 1885”.

Evidently, the Great Famine of the late 19th century was largely caused by the sudden disappearance of the local bison populations, depriving the First Nations of the Plains of their main source of food, clothing, and shelter. According to the analysis of Cree-Saulteaux scholar, Blair Stonechild, in just five years after 1880, the population of the Plains’ First Nations fell from 32,000 to 20,000 people. In this context, Macdonald took advantage of the weakened population to jump-start his National Policy and rapidly expand the Canada Pacific Railway.This pattern of sadistic power would continue within Canada's residential schools, known for their neglect and abuse,introduced by Macdonald as a national assimilation program in 1883.

Photo via Reuters | Canada's Prime Minister Justin Trudeau visits the Cowessess First Nation

Today, a newfound awareness of tragedy calls for the decolonisation of public spaces, intending to uncloak the invisibility of Indigenous memory. For instance, in 2017, the Ontario Elementary Teacher’s Federation proposed that school boards rename buildings bearing Macdonald's name. This movement gained the support of many Indigenous leaders such as Heather Bear, vice-president of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations. However, despite his rhetoric of reconciliation, Justin Trudeau disavowed said movement in the context of federal government buildings. This illustrates the stark divide that still exists between Indigenous leaders and the prime minister’s office.

Modern debates

And yet, many historians have engaged in a general movement to re-evaluate the past in order to give more weight to interpretations of previously ignored or marginalised groups. Indeed, we are in a context where many, like Justin Trudeau, believe that the process of reconciliation with Indigenous peoples must be completed: to that effect, the number of those who oppose the celebration of John. A. Macdonald have surged in recent years, correlating his image directly to this dark period in Canadian history. In terms of formal acts of reconciliation, the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement is one of the largest class actionsettlements in Canadian history. Under this agreement, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was established, where the government provides funds to help collect information from witnesses, engage with marginalised communities, and educate the general public about the history of the abusive system.

Though progress has been made, persistent challenges remain in reconciliation matters between Ottawa and Indigenous communities. Evidently, figures of political history affect the living narrative differently depending on the given perspective of analysis and the context of the account. Thus, when it comes to teaching said topics in schools for instance, it's of utmost importance to emphasise the whole picture and break down bias, as in highlighting Macdonald’s achievements without omitting the generational harm on Indigenous groups. Macdonald’s racist policies remain at the heart of Canada’s reconciliation debates, Indigenous sovereignty movements, and struggles over systemic racism.