When you think of space exploration, your mind might leap to towering rockets, state-of-the-art labs, and billion-dollar budgets. All allude to the power of a few countries and giant agencies. Rarely do you picture a group of students in a small lab, huddled after lectures, sketching rover blueprints on scraps of paper, hacking together parts from wherever they can find them, and pushing forward through sheer will.

Reaching for the stars

South Africa is no stranger to space. SANSA, the South African National Space Agency, manages the country’s geomagnetic and satellite research programs, contributes to international projects, and has helped the nation earn a spot on the global stage. One such international project is the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), the world’s largest radio telescope. Under construction across South Africa and Australia, it is a collaborative effort of 16 nations. The SKA shows what becomes possible when countries unite in pursuit of knowledge. Built on African soil and rooted in African skies, it is a statement of global scientific solidarity. But beneath these monumental efforts, the lived experience for students in South Africa remains gritty. We face funding gaps, limited access to specialised components, and few institutional safety nets. The ecosystem that supports national space programs often feels worlds away.

For this reason, youth-led initiatives and student projects, grounded in desire for change, are of vital importance. We are part of the UCT Space and Astronomy Society, a student-led collective fuelled by a simple but defiant conviction: space isn’t just for the privileged few; it belongs to everyone. Curiosity and creativity do not respect borders or bank accounts. They are humanity’s birthright to pursue, even when the odds are stacked against us.

Launching from the margins

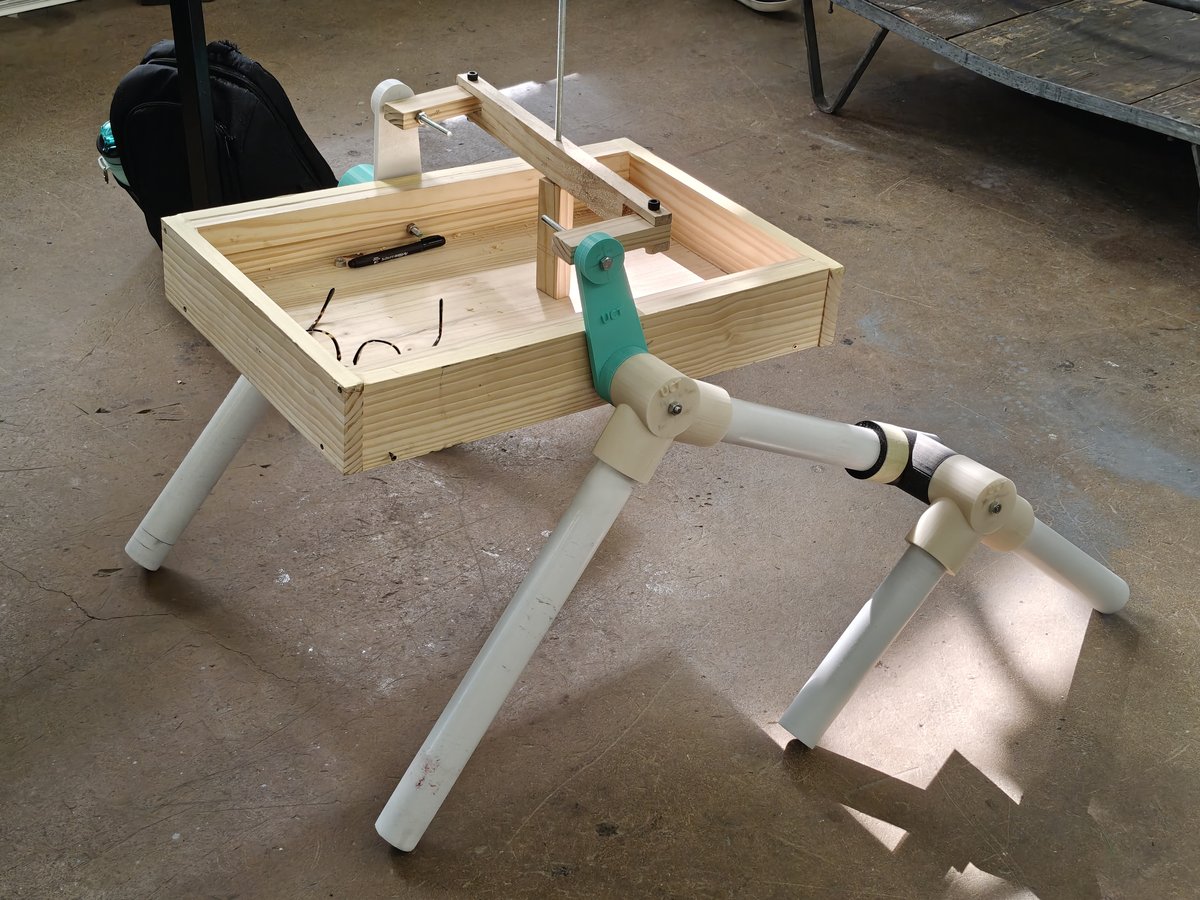

As citizens, youth, and, above all, astronomers, we work constantly to overcome barriers and prove that knowledge is a gift that belongs to all. This year, we accepted a challenge that would test every part of that belief: to design and build a Mars-style rover. A project like this demands technical skill, innovation, and relentless grit. As youth in other regions are encouraged to explore, funded for initiatives and supported by institutions, we face a dearth of support, evolving our goal into more than an academic project.

Building a rover at the bottom of Africa represents an act of rebellion and a rebuttal of the status quo. More than a technical endeavour, it is an act of resistance and resolve. It forces us to confront what it means to pursue space exploration from the margins, where resources are scarce and opportunities often feel out of reach.

One specific challenge we faced was sourcing the components needed to get the rover moving. Motors, sensors, and other critical parts repeatedly went out of stock, forcing us to reorder multiple times or piece together solutions from different suppliers. With tight budgets entirely covered by our own Society funds and strict functional requirements, we had to improvise constantly, finding creative ways to make every part work. Each late-night fix and brainstorming session became more than just a step in construction — it became a lesson in resilience and problem-solving, showing how passion and ingenuity can overcome the lack of structural support.

As a member of the Electronics and Software sub-team reflected, “I came for the experience, stayed for the chaos. No funding, no fancy tools, no safety nets — just late nights and stubbornness. And somehow, that was enough. The rover became proof that passion can beat structure.”

We are carving out space for ourselves in a field that doesn’t always make room. Every improvised fix, every late-night brainstorming session, every setback that transformed into a breakthrough is a quiet act of refusal, a reminder that the narrative of space exploration is not finished until we are in it.

From campus corners to cosmic conversations

We are not here to mimic the giants. We are here to reshape what participation means. Students in our team come from all disciplines — engineering, physics, computer science, design — demonstrating how space demands collaboration that transcends silos. This multidisciplinary nature embodies the spirit of ubuntu philosophy, encapsulated by the phrase “I am because we are”.

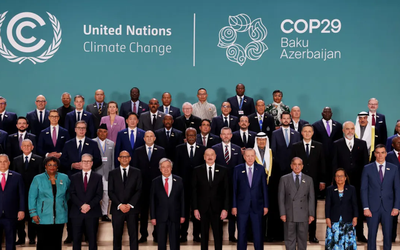

That vision of shared presence in space for Africans is not just something our team at UCT believes in. When Africa hosted the International Astronomical Union’s General Assembly for the first time, it was not only a celebration of science, but a clear signal for the cosmos to make space for African voices. Whilst we laboured over building a rover in the corner of a campus lab, the assembly was a nice, quiet affirmation that we are not working in isolation.

Our rover is a declaration of agency. In every line of code and 3D-printed part, it proclaims that curiosity is not the privilege of the few. This rover will never leave Earth — not for lack of ambition, but because it embodies something far greater than physical travel. It is a launchpad for imagination and possibility, a testament to ambition unfettered by circumstance. From South Africa, we are sending a message across the void: we are here, we belong, and the future of space will be richer with our voices.

Space is not just the final frontier, it is the next global challenge. We are ready to meet it head-on.