The two-month conflict between Hezbollah and Israel that raged from September 2024 to late November reshaped Lebanon’s political landscape. Hezbollah, which had been the deciding power in political appointments since the end of the civil war in 1992, made rare political concessions that led to the election of both a president and prime minister that are aligned with opposition blocs after years of blocked appointments. So far, this cabinet has ushered in a renewed period of stability and optimism in Lebanon. Yet Lebanon’s “new era” hangs by a thread. Constant bombardment in the South by Israeli forces threatens reconstruction efforts, while the issue of disarming Hezbollah — who backtracked on the terms dictated in the ceasefire agreement — is a cause of tension that may blow over into open armed conflict. This state of contrasting realities between Southern Lebanon and other regions could lead the country into true stability or chaos.

Reconstruction and revitalisation

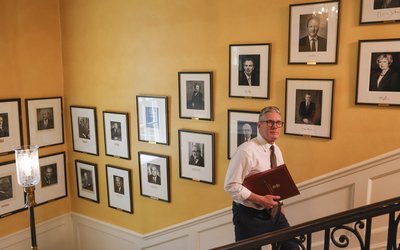

Current Lebanese Prime Minister Nawaf Salam has initiated several projects to rebuild Lebanon’s war-torn infrastructure, ranging from multiple public works initiatives, bridge rehabilitation projects, to a push for revitalising Lebanon’s public transport system, supported by a $250 million grant from the World Bank for reconstruction. Since then, the World Bank has predicted a 4.7% GDP growth for Lebanon this year. Beirut Souks, a high-end commercial district in Beirut’s Downtown, was recently reopened after a period of no activity following the 2019 financial crisis. On Beirut’s streets, there appears to be a new sense of safety; security forces display stronger regard for upholding order, with regular checkpoints to crack down on illegal activity and ensure road safety. All this is reflected in recent Gallup polling showing a record 62% of Lebanese adults supporting the government, a sharp increase from the 16% in support just last year.

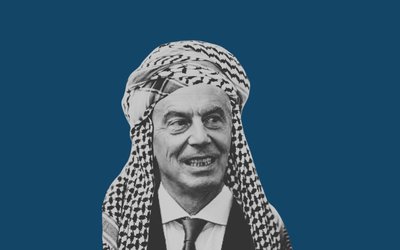

Politically, the Serail has taken a remarkably strong position on Hezbollah, formulating a plan to confiscate all its weapons, including ones of its allies like the Palestinian militias that control Palestinian refugee camps around the country. A number of factions in the camps have already handed over weapons peacefully. Hezbollah, instead, defiantly opposes the government’s position. Hezbollah’s new Secretary-General, Naim Qassem, has warned the government of retaliation if it attempts to go through with disarming Hezbollah. Salam has refused to backtrack, promising to implement the decision by the December 31st deadline his cabinet agreed on.

The tension between the two also stems from Salam’s efforts to free public institutions from Hezbollah’s control. This goal is both strategic and practical: the government plans to build a new civilian airport north of Beirut, since Lebanon’s only existing civilian airport is located in a Hezbollah stronghold in the south of the city. This has created a precarious situation, with the risk of an internal armed conflict growing increasingly likely.

A political tightrope

The situation in southern Lebanon remains critical. Daily Israeli airstrikes hit many parts of the deep south, aimed at dismantling Hezbollah’s remaining military infrastructure. Such bombings add strain to the fragile balance of national unity that the current government is still struggling to maintain. By tolerating these strikes against the militia, the government risks appearing complicit in attacks carried out on its own soil.

On October 11, a strike in the village of Msaileh hit over 100 private construction vehicles meant for civilian reconstruction efforts, bringing tensions to a head. The inaction by the government threatened to reinforce Hezbollah’s standing within its Shia base, which has long felt marginalised by the central government. Such a reinforcement would appear only to be damaging to the government’s legitimacy, built on the solid idea of national unity. Indeed, one of the main reasons Hezbollah commands such support among Shia groups is its position as a protector in the absence of strong leadership from the government.

As Salam remains intent in his intentions to demilitarise Hezbollah, an internal conflict in Lebanon seems only more likely. Hezbollah will undoubtedly use continued Israeli airstrikes as a means to build legitimacy in the postwar scene and remain, in the eyes of its supporters, the only real defender of the South. This increased polarisation might harm any attempt at national reconstruction and ultimately threaten the rare opportunity which the government now has to create a unified framework for growth. In short, it would doom Lebanon’s chance at revitalisation, bringing another round of fervent sectarianism upon the nation.

The way forward

The opposition groups, which make up the main support base for Salam’s government, should focus on fostering reconciliation through state institutions. Each of these parties represents a different religious sect, and they must be cautious not to let the temporary sense of balance among sects drive short-sighted political actions. They should instead focus on extending this balance to Shias and avoid framing the new political order as a victory over Shias, as it only achieves antagonising a sizable portion of the population, increasing the threat of communal violence.

Tools to promote safety and wellbeing, in the form of providing immediate aid to civilians or repairing destroyed houses, should be used to mitigate Hezbollah’s influence in the south, returning legitimacy to the government.

The government should remain firm on demilitarising Hezbollah, but must also present itself as a unifying force, one that includes Shia voices and meaningfully responds to the economic struggles faced by the country as a whole. Furthermore, the government needs to take a firmer stand on enforcing the ceasefire between Hezbollah and Israel. It must hold Hezbollah accountable to the agreement while working with international partners to bring an end to Israeli airstrikes in the South.

External actors, like the U.S. and European Union, should launch a two-pronged strategy to aid the government’s efforts by placing diplomatic pressure on the militia group to disarm and financially assist the towns in the South. This could be done by tagging certain EU aid to Lebanon — which amounted to over 100 million euros in 2024 — for projects in affected areas.

If this fails, armed conflict seems likely. The shape of this conflict will most likely take the form of regular clashes between the Lebanese military and Hezbollah forces over a full-blown civil war. The situation would be akin to that of the May 7th clashes in 2008, when Hezbollah occupied large parts of Beirut and clashed with the Druze (a minority religion in the Levant) in their mountain regions. The consequences of this conflict would be wide-ranging. It would put Lebanon’s post-war progress into peril and solidifying the religious divisions within the country. This could possibly lead to a period of rearmament by opposition groups to counter Hezbollah’s internal military dominance.

Lebanon’s post-war era will be determined in the coming months. The actions and rhetoric of the Serail hold the power to sway the country either direction. By extending a genuine olive branch, an almost unprecedented period of national unity and stability could be achieved, overcoming Lebanon’s decades old sectarian tightrope. Prosperity for all is in reach.